Git Explained: Understanding the Internals

While using Git commands effectively is essential, understanding how Git works internally unlocks its full potential, especially when managing complex projects or collaborating within large teams. This guide moves beyond basic usage to explore Git's core concepts and underlying mechanisms. By understanding Git's operations behind the scenes, we can harness its power more effectively.

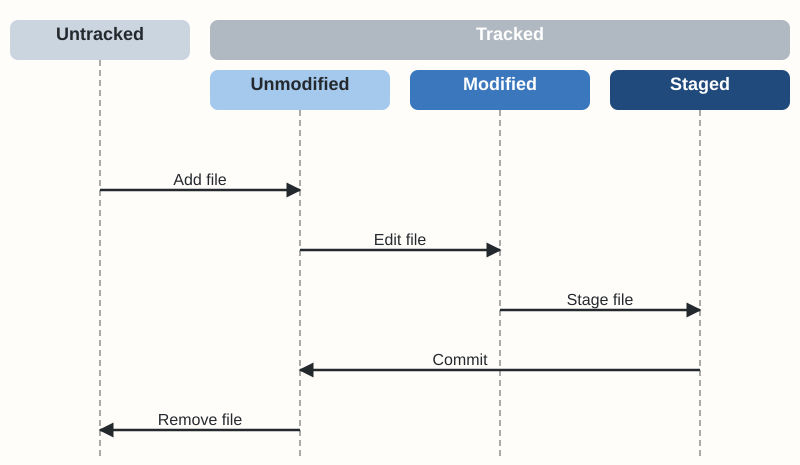

The File Lifecycle in Git

In Git, every file in your working directory falls into one of four main states. The journey from modifying a file to saving it involves distinct steps:

- Untracked: Files present in your working directory but not yet part of Git's tracking system. These are typically new files or files explicitly ignored by Git.

- Unmodified: Files that Git is tracking, but which haven't changed since the last commit. They are part of the repository's current snapshot.

- Modified: Tracked files that have been altered since the last commit, but whose changes have not yet been marked for inclusion in the next commit.

- Staged: Modified files whose current versions have been marked ("staged") to be included in the next commit snapshot. The

git addcommand moves changes to this state.

These states form a cycle as you work on your project:

New files start as Untracked. Using git add tells Git to start tracking them, moving them initially to the Staged state for the first commit, and subsequently to the Unmodified state after committing.

Editing an Unmodified file transitions it to Modified. You then use git add again to stage these specific modifications, moving the file to the Staged state. Staging allows you to carefully select which changes will be part of the next commit – think of it as preparing items for a package before sealing it.

Finally, git commit takes all changes currently in the staging area and records them as a new permanent snapshot in the repository's history. After the commit, the files involved return to the Unmodified state, ready for the next cycle of changes. Removing a tracked file also marks it as a change (deletion) that needs to be staged and committed.

This lifecycle provides precise control over version history, allowing for organized and meaningful commits.

Behind the Scenes: Git as a Content-Addressable Store

At its core, Git functions like a sophisticated content-addressable filesystem, essentially a key-value store. Every piece of data (file content, directory structure, commit information) is stored as an object with a unique key. This key is a SHA-1 hash (a 40-character hexadecimal string) calculated based on the object's content.

This design provides several benefits:

- Integrity: If the content changes even slightly, the hash changes, ensuring data integrity.

- Efficiency: Identical content (like an unchanged file) is stored only once, referenced by its unique hash. Retrieving any object using its hash is extremely fast.

This key-value structure is the foundation for Git's speed in operations like branching and merging.

The .git Directory: Your Repository's Brain

When you initialize a repository using git init, Git creates a hidden .git directory. This directory contains the entire history and metadata of your project – commits, branches, remote repository addresses, configuration, and the core object database.

git init

Now, let's add some files to the repository:

# Add a file and commit it

$ echo "# My Project" > README.md

$ git add README.md

$ git commit -m "Initial commit"

# Add another file in a subdirectory

$ mkdir src

$ echo "print('Hello, World!')" > src/main.py

$ git add src/main.py

$ git commit -m "Add main.py"

Exploring the .git Directory: The Repository's Core

The hidden .git directory is the heart of your Git repository. It contains all the information Git needs to track history, manage branches, and store your project's data. Listing its contents reveals several subdirectories and configuration files:

$ ls .git

shell@ branches COMMIT_EDITMSG config

shell@ description HEAD hooks

shell@ index info

shell@ objects refs

The objects directory is crucial for understanding Git's storage model. It acts as Git's internal database – a content-addressable key-value store. This directory contains the core Git objects:

- blobs (file content)

- trees (directory structure)

- commits (snapshots)

A look at the objects folder shows the storage strategy of Git:

$ ls .git/objects

shell@ 09 2a 2c

shell@ 3e a2 a5

shell@ fa info pack

Git stores every object based on a unique key: its SHA-1 hash, a 40-character hexadecimal string (e.g., 2ab2fee78d2407501ebddba6d6a6a63759ace7ac). This hash is calculated from the object's content. To organize storage, Git uses the first two characters of the hash as a subdirectory name (e.g., 2a) and the remaining 38 characters as the filename within that subdirectory (e.g., b2fee7...).

These SHA-1 hashes are the unique identifiers you see for commits in the output of git log:

$ git log

shell@ commit a50d7c3e152319b9059831f57bfa3f20e203ed55 (HEAD -> main)

shell@ Author: johndoe <john@example.com>

shell@ Date: Thu Apr 17 07:31:32 2025 +0200

shell@ Add main.py

shell@ commit 2ab2fee78d2407501ebddba6d6a6a63759ace7ac

shell@ Author: johndoe <john@example.com>

shell@ Date: Thu Apr 17 07:23:45 2025 +0200

shell@ Initial commit

Dissecting Git Objects with git cat-file

To inspect the content of these stored objects, you can use the low-level command git cat-file -p <hash>. You typically only need to provide the first few characters of the SHA-1 hash.

Let's examine the commit object a50d7c3e...:

$ git cat-file -p a50d7c3e

shell@ tree 2cdb2f6dbcfc51b8814a755311d2963be654a95c

shell@ parent 2ab2fee78d2407501ebddba6d6a6a63759ace7ac

shell@ author johndoe <john@example.com> 1744867892 +0200

shell@ committer johndoe <john@example.com> 1744867892 +0200

shell@ Add main.py

[!NOTE] While full SHA-1 hashes are 40 characters, Git usually only requires the first 7 characters (or even fewer in small repositories) to uniquely identify an object. Using 7-10 characters is generally safe practice.

Git primarily manages four types of objects:

- Commit Object: Contains metadata (author, committer, date, message), a pointer to one top-level tree object, and pointers to one or more parent commits. Represents a snapshot in time.

- Tree Object: Represents a directory. Contains pointers (by hash) to blobs (files) and other trees (subdirectories) within it, along with file/directory names and modes.

- Blob Object: Stores the raw, uninterpreted content of a file. Contains no metadata like filename.

- Tag Object: Points to a commit object, usually marking a release. Annotated tags are stored as separate objects with additional metadata.

The commit object (a50d7c3e) points to a tree object (2cdb2f6d). Let's inspect that tree:

$ git cat-file -p 2cdb2f6d

shell@ 100644 blob a2beefd59223ea16000788d77e62f96bdaf23c7c README.md

shell@ 040000 tree 3ebf4cba99e8c0453e20f458506e029dea2ab4cd src

This tree object lists its contents: the README.md file (represented by a blob) and the src directory (represented by another tree). Let's look at the README.md blob:

$ git cat-file -p a2beefd5

shell@ # My Project

As expected, the blob contains the raw content of the file. We can also inspect the src tree:

$ git cat-file -p 3ebf4cba

shell@ 100644 blob 09907203e86ff6490c525b989c65bdef64aa706a main.py

This demonstrates how Git links objects together to represent the entire project state for a given commit.

A More User-Friendly View: git show

While git cat-file is excellent for understanding Git's internal structure, the git show <hash> command provides a more human-readable summary, particularly for commits. It displays the commit metadata, message, and the changes (diff) introduced by that commit compared to its parent(s).

$ git show a50d7c3e

shell@ commit a50d7c3e152319b9059831f57bfa3f20e203ed55 (HEAD -> main)

shell@ Author: johndoe <john@example.com>

shell@ Date: Thu Apr 17 07:31:32 2025 +0200

shell@ Add main.py

shell@ diff --git a/src/main.py b/src/main.py

shell@ new file mode 100644

shell@ index 0000000..0990720

shell@ --- /dev/null

shell@ +++ b/src/main.py

shell@ @@ -0,0 +1 @@

shell@ +print('Hello, World!')

For everyday tasks like reviewing commit changes, git show is generally preferred. Use git cat-file when you specifically need to inspect the raw object data or explore the low-level object relationships.

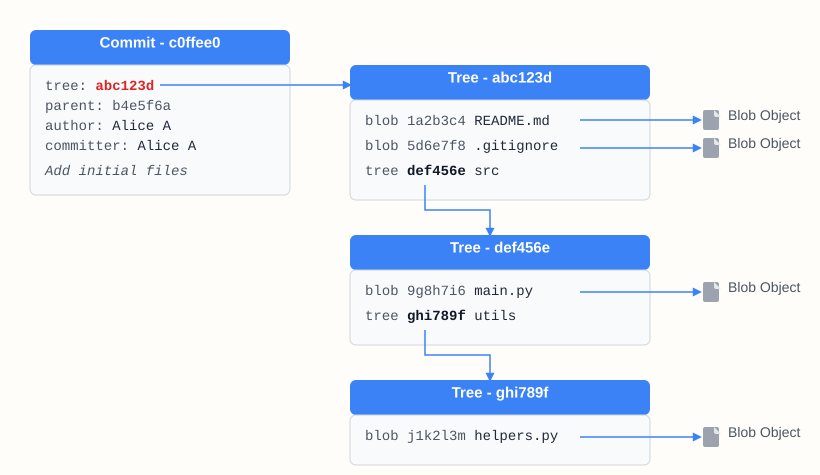

Understanding the Git Tree Structure

Git's object model creates a connected graph representing the project's history and content.

Commit, Tree, and Blob Relationships

- Commit: A snapshot identified by its SHA-1 hash. References exactly one top-level Tree representing the project root at that commit. Includes metadata and reference(s) to parent commit(s).

- Tree: Represents a directory identified by its SHA-1 hash. References Blobs (files) and other Trees (subdirectories) it contains.

- Blob: Represents file content identified by its SHA-1 hash. Stores only the raw data.

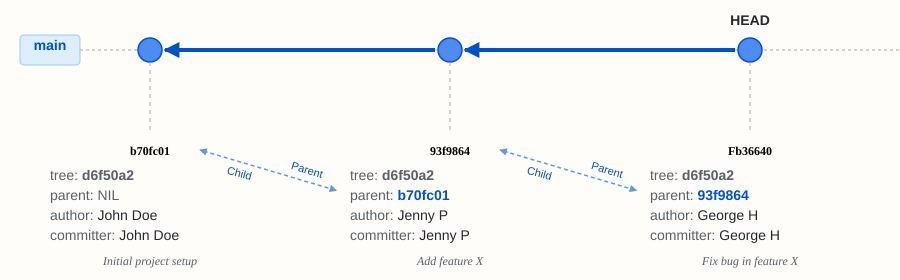

Parent-Child Commit Links

Project history unfolds through links between commits. Most commits reference a single parent commit – the snapshot that came immediately before it on that line of development. This chain of parent references forms the history of a branch.

Merge commits are unique because they reference two or more parent commits, signifying the point where different development histories were combined.

How Git Stores Trees and Blobs Efficiently

Git's storage mechanism is highly efficient due to its content-addressable nature and the way objects are linked:

Each commit points to a tree representing the project's state. This tree, in turn, points to blobs and other trees. Crucially, if a file's content (and thus its blob's SHA-1 hash) remains unchanged between two commits, both commits will ultimately reference the exact same blob object. Similarly, if a directory's contents don't change, its tree object will be reused.

Git only stores new objects for content that has actually changed. This reuse of unchanged blob and tree objects drastically reduces storage requirements and makes operations like checking out branches very fast, as Git only needs to update the files that differ.